Complex Sensing, Control Systems Enhance Safety

Image Source: MOLPIX/shutterstock.com

Original Article Written By Warren Miller, Edited & Updated by Mouser Staff

Edited May 26, 2020 (Originally published July 8, 2015)

In many industrial applications, it is critical to sense, log, and communicate data about environmental

conditions. Many industrial processes involve high temperature, high pressure, vibration, and corrosive gases or

liquids, but sensing is critical to controlling and monitoring these processes, usually in very harsh

environmental conditions. In many of these applications, control is a critical element in safety—for the

equipment, the process, or the operators. The weak link in many of these control systems is the sensing

function because they are typically needed in the harshest part of the harsh environment. Control systems can

often be located away from the harshest part of the environment, so they might not have as exacting requirements

as the sensing elements.

An illustrative example of a common harsh environment with exacting sensing and control requirements is in

down-hole drilling, where it is critical to accurately control the drilling or extraction process. Without

continuous control, the process might take longer, require more maintenance interruptions, or even damage

complex and expensive equipment. In the worst case, operators might be put in danger if the control system fails

to take critical corrective action. An attempt to save a few dollars on a lower-accuracy or less-reliable sensor

could eventually cost millions of dollars in lost time, equipment damage, or even operator injury or death.

Sensing requirements in a down-hole application can cover a very wide range. It's not unusual for sensors that

track temperature, pressure, resistivity, and even gamma-ray radiation levels to be found in down-hole

applications (Figure 1). These sensors clearly need to stand up to the high temperatures,

pressures, vibration, and corrosives found in a typical down-hole environment, but accuracy can be important as

well. Small changes, detected early, can make it easier for the control process to identify trends that could be

an early-warning sign of system stress that needs to be mitigated or controlled. Fortunately, sensors that can

withstand harsh environments are available as well as provide the accurate measurements required for advanced

control systems. Let’s review sensors that are critical to controlling and monitoring in harsh

environments.

Figure 1: Down-hole sensing is critical to safety and efficiency.

(Source: Ingvar Tjostheim/Shutterstock.com)

System Architecture for Harsh Environments

As mentioned, it is usually helpful to try to separate the sensing and control elements in a harsh environment

design. This places the more complex electronics at a distance from the harshest portion of the environment and

puts the more-robust sensors in the most challenging area. Usually, however, some amount of control is required

near the sensors to manage the data collection and the transmission of data to the remote control system.

Additionally, it might be important to log data in or near the sensor pod so that a complete record of the

process is available for efficiency measurements or in the event of a failure (similar to the use of a black box

in an aircraft to help determine the root cause of errors or failures after the fact). Logging data will also

require some amount of control to manage the process.

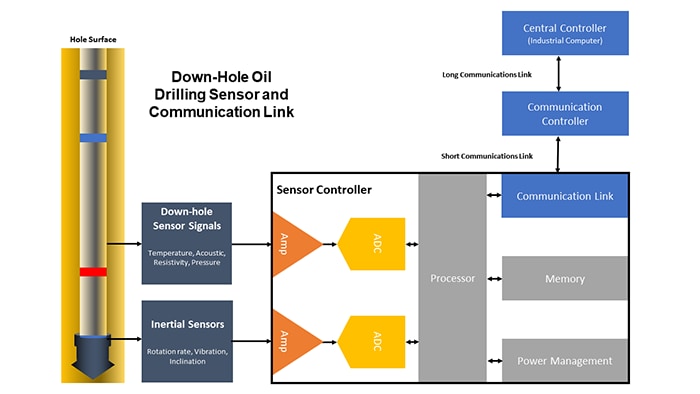

One approach to architecting the system is to put simple controllers near the sensing elements to do the minimum

required to implement the communications and logging functions (Figure 2). Multiple sensors are

located at the sensor package near where the environmental sensing occurs. A local sensor controller can capture

sensor readings and process them to reduce the data transmission overhead. A communications controller can be

located some distance away from the sensor package to somewhat reduce the harsh environment requirements. The

bulk of the data processing and algorithmic processing can be done by a central controller, located remotely,

perhaps using a common industrial computer. Communications between the controllers can be done wirelessly, if

the environment allows, or via electrical or fiber-optic cables.

Figure 2: Example system architecture for down-hole sensor application,

assume fiber optics are preferred, due to their ability to communicate over long distances with minimal

electrical interference. (Source: Mouser Electronics)

Sensors and the Signal Chain

Temperature sensors are probably the most well-known sensor type, with platinum-based sensing, that changes

resistance with temperature, very common. For example, Honeywell 700 series thin film platinum sensors cover a

temperature range from -70°C to 500°C and work in even the harshest temperatures. Other sensors for

pressure, magnetics, fluid flow, gas, or position can be co-located in a rugged sensor enclosure to provide some

protection from vibration and mechanical stresses. Sensors will typically need to be monitored by an electronics

signal chain that includes amplification, analog-to-digital conversion, and perhaps even some signal processing

to extract the signal from the noisy environment. It can be a challenge to find the components needed to

implement this section of the design that operate at a high-temperature range, but fortunately some

manufacturers offer an extended temperature range for the types of products needed for sensing in

high-temperature applications.

Texas Instruments provides a selection of signal-chain-oriented devices that operate over an extended temperature

range from -55°C to 210°C. These products can create the needed input signal chain starting from a

high-temperature operational amplifier (op amp) such as the TI OPA 2333. The output of the op amp can then feed

a high-temperature analog-to-digital converter such as the TI ADS1278. Because these products are offered over

such a wide temperature range and come in robust ceramic packages, they can be used for sensor applications

within even very harsh environments.

Control Systems Architecture

Using the example design in Figure 2, design engineers need three levels of control capability.

A controller with some signal-processing capability is necessary nearest the sensors. Further from the sensor,

in the communications package, a simple controller to handle the communications and logging functions is needed.

Finally, at the other end of the communications transmission line, an industrial computer is needed to provide

the high-level algorithmic control and monitoring for the drilling process.

Sensor control and monitoring are the most processing-intensive and also require the most robust controller. One

candidate for this task is the Texas

Instruments TMS320F2812 Digital Signal processor. It can operate over the extended temperature range

(-55°C to 210°C) required for the sensor package located in the harshest portion of the environment. The

DSP capabilities allow it to process data before sending it to the communications package, reducing the overall

bandwidth required—a significant efficiency boost.

The communications controller can be a much simpler processor, perhaps even a 16-bit MCU such as the NXP Semiconductor

S9S12G128AMLH.

With less-stringent temperature requirements for the controller, an operational temperature of up to 105°C

will be sufficient. This class of MCU has all the features required to manage the communications traffic from

the sensor package to the system controller and to implement any needed data-logging functions.

The central controller has the least stringent requirements, so a standard industrial computer with plenty of

computation and storage capability such as the MYIR MYS-6ULX-IND is a good choice.

The MYS-6ULX-IND is for Industry 4.0 applications and based on i.MX6UL series processors. The MYS-6ULX-IND

can support -40°C to +85°C extended temperature operation, which makes the board suitable for industrial

control and communication applications.

The Communications Link

Getting the signal from the sensors all the way to the central controller will present a significant challenge.

The communications link could use fiber optics, electrical cable, or wireless depending on the distance required

and the characteristics of the environment. Clearly, wireless would present the least challenges as a connection

medium, but might not be possible in many environments where noise or obstructions can cause interference, such

as a down-hole application.

Fiber-optic cable and robust connectors are a useful communications option over long distances. Some fiber-optic

connector systems, such as the Molex LC2+

Metallic

Optical Connectors, use a special high-temperature metal body that withstands long-run operating

temperatures up to 150°C as well as sever shock and vibration exposure.

Electrical communications are appropriate over short distances if excessive signal noise and the risk of

combustion are not present. Serial transmission protocols can be used at low speeds (such as traditional UART

rates) or even up to 10-Gb Ethernet if very high bandwidth is required. With any wire-based communications

scheme, robust connectors must be used to withstand high temperatures or severe vibrations. For example,

the CeeLok

FAS-T connector

from TE Connectivity can be used in a variety of communications systems with Cat 5e (for 1Gb

Ethernet) or Cat 6a (for 10Gb Ethernet) cabling. In the example design of Figure 2, a wired

connection from the sensor package to the communications controller would be appropriate. Depending on the

number of sensors and monitoring frequency, a simple UART or a low-speed Ethernet protocol could be implemented.

Conclusion

Harsh environments, as

represented by a down-hole drilling application, can severely constrain a design engineer's implementation

choices in comparison to a traditional environment. Components with extended temperature ranges, even up to

200°C, make it possible to construct robust and complex sensing systems in very challenging environments. By

distributing communications and data-logging functions remotely from the most severe conditions, a wider range

of products can be used, where devices with a maximum temperature of 85°C or 105°C will be adequate.

This type of distributed approach to system implementation can be extended to a wide variety of applications,

even where the environmental challenges are perhaps only as severe as for a cellular base station or a chassis

control card for a rack of high-performance servers.

Slovakia

Slovakia